This is the 2nd article about my experience implementing custom visualizations for the Boost.Unordered containers in the Visual Studio Natvis framework. You can read the 1st article here.

This 2nd article is about the open-addressing containers, which all have shared internals. These are the boost::unordered_flat_{map|set}, boost::unordered_node_{map|set}, and boost::concurrent_flat_{map|set}. I’ll take you through my natvis implementation in this article, omitting the methods and details that the 1st article already covered.

Importantly, this article will discuss fancy pointers. This includes an overview of what they are, how they’re injected into Boost.Unordered, and how I was able to implement a natvis solution that’s abstracted over all possible fancy pointer types. If you’re still reading and you haven’t yet read the 1st article, I recommend doing that before this one. This current article won’t make as much sense without it.

This work has been sponsored by The C++ Alliance.

Comparing to the closed-addressing containers

My general approach for displaying the open-addressing containers is the same as my previously described approach for displaying the closed-addressing containers.

- Display the function objects and other special container helpers.

- Write a visualization that iterates the general-purpose implementation underlying the container.

- Separate the map and set visualizations by duplicating the entire

<Type> element, to ensure each map element item has its display name set to [{key_name}] by default.

The open-addressing containers don’t have the option for “active” and “spare” function objects, so displaying the hash_function and key_eq is much simpler. However, the open-addressing containers will have statistical metrics available in Boost 1.86 (see docs here), which adds an extra thing to implement.

Most notable about the open-addressing containers are their optimizations when SIMD operations are available. The internal layout of the container metadata varies according to whether or not SIMD acceleration is used, but the iteration algorithm is generic and works with both layouts. The SIMD and non-SIMD specifics are encapsulated in two intrinsics called match_occupied() and is_sentinel() that I’ll discuss later.

On the other hand, for both closed-addressing and open-addressing containers, fancy pointers complicate the situation. I’ll briefly introduce fancy pointers, then I’ll discuss everything about the open-addressing natvis implementation without fancy pointers, and lastly, I’ll try to combine the fancy pointers with the open-addressing natvis. (Spoiler: It works, but it took many tries.)

Fancy pointers and Boost.Unordered

A fancy pointer is a class that has the same operations as a pointer, and can be used interchangeably where a pointer would be used. You can dereference them, increment them, and compare them, among other operations. Classically, many STL iterators generally behave like pointers and can be considered as fancy pointers. The Boost.Interprocess library also contains some fancy pointers like intrusive_ptr and offset_ptr. The Boost.Unordered open-addressing containers are designed to be used with any allocator using normal or fancy pointers.

As I already alluded to, the “injection site” of the pointer type is through the container’s allocator. Effectively, if your allocator A has an alias called A::pointer then this is used as the pointer type, otherwise the pointer type defaults to A::value_type*. This logic is all contained in std::allocator_traits<A>.

In my mission to visualize all Boost.Unordered containers in the natvis framework, I also wanted to support the containers that use fancy pointers. To achieve this goal, it’s important to understand where and how these type aliases are injected. Let’s set aside the discussion of fancy pointers for now, and get back to it later.

Generically accessing integrals and atomics

(Note: All types I name here without qualification are internal types, using the boost::unordered::detail::foa namespace. These details aren’t strictly important, but I don’t want to leave you lost in my explanation.)

Some extra detail: The container implementation, a type called table_core, gets iterated by using its members arrays.elements_ and arrays.groups_. The member arrays.groups_ is of type group15<>, whose implementation differs between the SIMD and non-SIMD code. I’ll get to this in the next section.

Importantly here: The specific instantiation of group15<> differs between boost::concurrent_flat_{map|set} and the other open-addressing containers. A group15<> holds an array m, either containing plain_integral values or atomic_integral values, which are structs that either hold an integral or a std::atomic. How can I generically access either one of these?

<Intrinsic> elements! I created the following 2 intrinsics, inside their respective <Type> elements.

<!-- Inside <Type> for `plain_integral` -->

<Intrinsic Name="get" Expression="n" />

<!-- Inside <Type> for `atomic_integral` -->

<Intrinsic Name="get" Expression="n._Storage._Value" />

With this, I can generically access the integral value stored inside, regardless of which kind it is. In a group15<>, if I want the value at index 0, I call m[0].get() and it works in all cases. Yes, this involves creeping into the internals of the MSVC implementation of std::atomic, which may not be completely desirable in general, but natvis is meant for MSVC-specific debugging.

Now onto the SIMD portion.

Some consideration for SIMD

The type group15<> has 2 functions that are required for iterating the table, match_occupied() and is_sentinel(). These functions have a different implementation in the SIMD and non-SIMD cases. Again, I want to do things generically.

I won’t explain the entire implementation, but here is an overview of what it looks like. Internally these all use the above get() intrinsics from the previous section, looking like m[i].get().

<Intrinsic Name="__match_occupied_regular_layout_true" Expression="..." />

<Intrinsic Name="__match_occupied_regular_layout_false" Expression="..." />

<Intrinsic Name="match_occupied" Expression="regular_layout

? __match_occupied_regular_layout_true()

: __match_occupied_regular_layout_false()" />

The type group15<> has a static constexpr boolean called regular_layout to denote which implementation to use, whether it’s using SIMD-accelerated metadata or not. I implemented each of the cases as their own intrinsic, and used a ternary expression to decide which one to call. I did the same for is_sentinel(), not shown here. Ultimately it’s a simple solution, but it wasn’t obvious at first.

<Intrinsic> elements cannot have a Condition attribute, otherwise I would have implemented 2 copies of match_occupied() directly, with opposite conditions.

Also importantly, both versions of the algorithm are semantically valid in both cases, even though one of them gives the wrong result. If that was not the case, I could have implemented 2 copies of match_occupied() with the Optional="true" attribute. One of them would fail to parse and the other would succeed. This is analogous to SFINAE in C++, where a specific instantiation can fail, but the program as a whole does not fail. Instead, another instantiation is chosen.

More helpers to iterate the table

In the last article I showed a simplified diagram of the internal layout. This time, any diagram I show would misrepresent the structure. I will instead direct you to a blog post by Joaquín M López Muñoz titled “Inside boost::unordered_flat_map”.

For the natvis implementation, I just translated the C++ algorithm into natvis syntax directly. After creating the group15<> helpers above, this turned out quite easy. The last facility I needed was a countr_zero() function implemented in natvis. In an earlier version, I implemented this procedurally inside the <CustomListItems> logic, complete with <Loop> and <Exec> elements, but I decided to do this with an <Intrinsic> instead.

I started with a helper <Intrinsic> called check_bit() to see if a particular bit is set. In C++ it would look like this.

bool check_bit(unsigned int n, unsigned int i) {

return (n & (1 << i)) != 0;

}

Translated into natvis it looks like this.

<Intrinsic Name="check_bit" Expression="(n & (1 << i)) != 0">

<Parameter Name="n" Type="unsigned int" />

<Parameter Name="i" Type="unsigned int" />

</Intrinsic>

<Intrinsic> elements don’t allow looping, and C++ doesn’t have any “list comprehension” facilities, so I needed to unroll the loop by hand. Here is what a looping implementation of countr_zero() would look like in C++, using my check_bit() helper.

int countr_zero(unsigned int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < CHAR_BIT * sizeof(n); ++i) {

if (check_bit(n, i)) {

return i;

}

}

return CHAR_BIT * sizeof(n);

}

Instead of this code above, I unrolled the loop in a natvis <Intrinsic> element below. It’s ugly, but it gets the job done. I’ll spare you the entire thing, but here’s what it looks like.

<Intrinsic Name="countr_zero" Expression="

check_bit(n, 0) ? 0 :

check_bit(n, 1) ? 1 :

...

check_bit(n, 31) ? 31 : 32

">

<Parameter Name="n" Type="unsigned int" />

</Intrinsic>

With this done, iterating the table is as simple as translating the C++ code into natvis. Of course this isn’t trivial, but I didn’t need a firm understanding of the internals conceptually. I just needed to combine [container]::begin(), [iterator]::operator++(), and [iterator]::operator*() into 1 big loop.

Suddenly, fast inverse square root appears

When Boost 1.86 is released very soon, the open-addressing containers will be equipped with statistical metrics, on an opt-in basis. These should also be displayed in the natvis. These metrics are summarized as the average, the variance, and the deviation of a number of internal figures. Unfortunately for me, deviation = sqrt(variance). How can I calculate a square root manually here?

Immediately I knew that I needed to implement a 64-bit version of the Quake III “fast inverse square root” algorithm, but the question is where. If I implement this procedurally inside a <CustomListItems> element, then I’ll need to implement it twice, because of the desired visualization structure which requires 2 separate <Synthetic> elements. That’s not very maintainable. Ultimately I used my most trusted tool, the <Intrinsic> element. I’m sensing a pattern here…

(Quick note: A <Synthetic> element allows you to synthesize a visualization item as if it were a data member of the class. Within the <Synthetic> element, you can give it a <DisplayString> and an <Expand> element with its own visualization items. These can be arbitrarily nested, giving the exact desired structure.)

Here’s my strategy: Create 2 helper <Intrinsic> elements to facilitate the reinterpret_casting, then create 2 more helpers for the “initial” and “iteration” step of the algorithm. Then create a final <Intrinsic> that puts it all together. The helpers looked like this. If you’re familiar with the algorithm, this should make perfect sense.

<Intrinsic Name="bit_cast_to_double" Expression="*reinterpret_cast<double*>(&i)">

<Parameter Name="i" Type="uint64_t" />

</Intrinsic>

<Intrinsic Name="bit_cast_to_uint64_t" Expression="*reinterpret_cast<uint64_t*>(&d)">

<Parameter Name="d" Type="double" />

</Intrinsic>

<!-- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fast_inverse_square_root#Magic_number -->

<Intrinsic Name="__inv_sqrt_init" Expression="bit_cast_to_double(0x5FE6EB50C7B537A9ull - (bit_cast_to_uint64_t(x) >> 1))">

<Parameter Name="x" Type="double" />

</Intrinsic>

<Intrinsic Name="__inv_sqrt_iter" Expression="0.5 * f * (3 - x * f * f)">

<Parameter Name="x" Type="double" />

<Parameter Name="f" Type="double" />

</Intrinsic>

Lastly, to put it all together, I decided on 4 iterations of the “looping step” of the algorithm. This gave me good enough results in my testing, where the result was precise to within 8 decimal places. I started with __inv_sqrt_init, and then fed __inv_sqrt_iter back in on itself 4 times. It looks like this.

<Intrinsic Name="inv_sqrt" Expression="__inv_sqrt_iter(x, __inv_sqrt_iter(x, __inv_sqrt_iter(x, __inv_sqrt_iter(x, __inv_sqrt_init(x)))))">

<Parameter Name="x" Type="double" />

</Intrinsic>

It has a certain beauty to it. I like the purity.

And with that, the statistical metrics could be visualized!

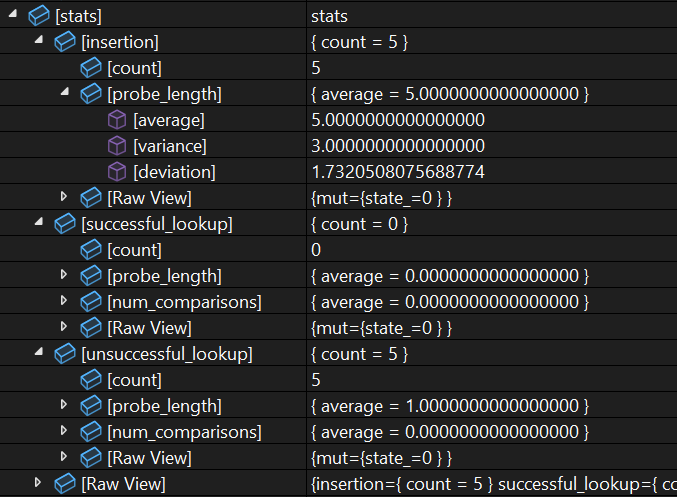

Below is a screenshot of the final version. I filled the stats with some garbage data for demonstration purposes only in this screenshot. Note that [stats] is just 1 of the items in the container visualization. It comes after the [allocator] but before the elements.

The items [insertion], [successful_lookup], and [unsuccessful_lookup] are actual subobjects of the larger stats object. Within each of them, [probe_length] and [num_comparisons] are both created with <Synthetic> tags, and do not exist as subobjects in the data. I visually expanded only one of the [probe_length] items in the screenshot, but all [probe_length] and [num_comparisons] items have the same format.

Back to fancy pointers

The open-addressing container implementation accounts for fancy pointers. For example, earlier I mentioned the arrays.elements_ and arrays.groups_ members, which are needed to iterate the table. The iteration actually calls arrays.elements() and arrays.groups(), which are fancy-pointer-aware getters. Let’s just talk about elements() for now, to simplify.

The member elements_ is of type value_type_pointer (a class-scope alias). This may be the raw pointer value_type*, but it also may be some type of fancy pointer that has value_type* as its underlying raw pointer type, depending on the allocator. The library uses boost::to_address() and boost::pointer_traits<>::pointer_to() to convert between fancy pointer and raw pointer types. In this case, elements() gives us boost::to_address(elements_), which always returns a value_type* no matter the pointer type in use.

The iterator operations make heavy use of these to_address() and pointer_to() conversions. The iterator also contains 2 data members, which may be raw pointers or fancy pointers. In order to iterate in the natvis implementation, I need to emulate the iterator operations and data.

Let’s start with some easier operations and see where we get.

Easier: to_address()

boost::to_address() essentially does the following.

- If it is passed a raw pointer

p, return the raw pointer.

- Otherwise return

boost::to_address(p.operator->()), which recurses until it eventually finds a raw pointer. (Or until it finds a compile error)

This means that the implementation relies on user-specified behaviour through a function. A natvis visualization cannot directly call p.operator->() because, as I discussed in the 1st article, natvis does not allow calling any C++ functions. I’ll solve this by creating a customization point. I’ll write a pair of <Intrinsic> elements using Optional="true", so that one of them always fails to parse and the other succeeds. Again, this is very similar to SFINAE in C++.

<Intrinsic Name="to_address" Optional="true" Expression="&**p">

<Parameter Name="p" Type="value_type_pointer*" />

</Intrinsic>

<Intrinsic Name="to_address" Optional="true" Expression="p->boost_to_address()">

<Parameter Name="p" Type="value_type_pointer*" />

</Intrinsic>

Some points about this to_address() overload set.

- A

<Parameter> can only have a fundamental type or a pointer type. If we’re using raw pointers, then value_type_pointer is already a pointer. But if we’re using fancy pointers, then we can’t take value_type_pointer by value since it’s a class type. We need to work around this and use value_type_pointer*.

- The expression

*p would succeed with both raw pointers and fancy pointers, but I need one overload to fail in any given case. I need a way to make a simple dereference operation fail with fancy pointers, so instead I use &**p. This will fail because the leftmost dereference will try to call the user-defined operator*() on the fancy pointer.

- This customization point requires the author of a fancy pointer type to create the intrinsic for their own type called

boost_to_address() that converts to the underlying raw pointer. This is the opt-in that would allow an author to use their type with this natvis implementation.

I would also need to create 2 similar overloads for group_type_pointer. I will need a similar customization point next(p, n) to replace operator+=(), but it turns out that it’s best for this to be a static function. I’ll get to that later.

Harder: Can we create a class type object in natvis?

The first step of the <CustomListItems> logic is emulating constructing the begin() iterator, storing some data that represents its state. Then later, we can mutate this state as we emulate the iterator’s operator++() and operator*().

I’ll start simpler. Let’s emulate the iterator’s p_ member. Effectively, assuming we have a value_type* called p as input, it’s constructed by calling to_pointer<value_type_pointer>(p), where to_pointer() is an internal library function that calls into pointer_to() deeper down. The member p_ will either be a raw pointer or a fancy pointer.

If p_ is a fancy pointer, then it’s a class type. Let’s explore how to create a class type object in natvis, using MyType as a stand-in for the fancy pointer type.

struct MyType {};

Let’s try creating an intrinsic that produces a MyType.

<Intrinsic Name="get_my_type" Expression="MyType{}" />

This yields a natvis error saying Error: unrecognized token, so this doesn’t work. What about the following?

<Intrinsic Name="get_my_type" Expression="MyType()" />

This gives an error saying Error: Implicit constructor call not supported., so this also doesn’t work. What about using reinterpret_cast? This requires a helper intrinsic. I’ll pass some already-created bytes and cast it to a MyType.

<Intrinsic Name="get_my_type_helper" Expression="*reinterpret_cast<MyType*>(&x)">

<Parameter Name="x" Type="uint64_t" />

</Intrinsic>

<Intrinsic Name="get_my_type" Expression="get_my_type_helper(0)" />

This actually works. But it only works for any type that’s the same size as uint64_t or smaller. For anything larger, the associated item is displayed as <Unable to read memory>.

But that might be fine. Maybe we can specify that we only support fancy pointer types 8 bytes in size or less. Or maybe we can give get_my_type_helper() a <Parameter> of an array type for larger sizes somehow. We can’t use any class types as parameters, but again, that could be fine.

This answers the question. It looks like we can create a class type object in natvis.

Here’s the real problem.

We can’t create a class type object in natvis

Even if the scenario above ends up working, we still can’t get past the barrier presented below. We need to emulate the iterator’s stored data by creating some <Variable> elements in the <CustomListItems>. Then we’ll modify this data to emulate incrementing the iterator. Our iterator stores 2 fancy pointers, which can be anything and can contain anything, so we can’t deconstruct it any further in the general case.

Let’s assume one of the fancy pointer types is a MyType from the previous section. Inside the <CustomListItems> element, let’s create one as a <Variable>.

<Variable Name="var" InitialValue="get_my_type()"/>

We get an error saying Error: Only primitive and pointer-type variables are supported; got 'name.exe!MyType'., so this doesn’t work. No class type <Variable> elements allowed.

Can we get around this? Let’s try creating a uint64_t as storage, then writing a helper to return a MyType* instead. Then we have access to a MyType object through the pointer.

<Intrinsic Name="cast_to_my_type" Expression="reinterpret_cast<MyType*>(p)">

<Parameter Name="p" Type="uint64_t*" />

</Intrinsic>

...

<Variable Name="storage" InitialValue="(uint64_t)0"/>

<Variable Name="var" InitialValue="cast_to_my_type(&storage)"/>

Natvis doesn’t allow this, giving a longer error that says Error: Using an iteration variable to store the address of an iteration variable an object optimized into a register is not supported. [sic]. So clearly this is explicitly not allowed.

I’m at the bargaining stage now, or maybe I’ve been there for a while.

What if I don’t store the reinterpret_casted value in a variable, but instead just use it to modify the data as needed? For argument’s sake, let’s say MyType has an int member called value. In a real case we won’t know the internals of the type, but I want to reduce it to a simpler problem for now. I’ll try something like this to see if it works.

<Variable Name="storage" InitialValue="(uint64_t)0"/>

<Item>cast_to_my_type(&storage)->value</Item>

<Exec>cast_to_my_type(&storage)->value = 5</Exec>

<Item>cast_to_my_type(&storage)->value</Item>

I would expect this to print 2 items to the visualization, with values of 0 and 5, respectively. But no. There’s another error. Error: Side effects are not supported in this context.. Maybe wrap the side effect in another <Intrinsic> that’s marked with the attribute SideEffect="true"?

<Intrinsic Name="modify" SideEffect="true" Expression="my_type->value = 5">

<Parameter Name="my_type" Type="MyType*" />

</Intrinsic>

...

<Variable Name="storage" InitialValue="(uint64_t)0"/>

<Item>cast_to_my_type(&storage)->value</Item>

<Exec>modify(cast_to_my_type(&storage))</Exec>

<Item>cast_to_my_type(&storage)->value</Item>

This gives the same error. Everything similar that I have tried leads to this type of error.

This is where I got stuck.

Getting unstuck, calling a lifeline

I originally wrote this article and ended it right here. I discussed this problem with Joaquín, and he suggested another approach. After taking my thoughts and his thoughts and boiling them down, I realized that I was over-complicating the situation. Instead of trying to store a uint64_t and reinterpret_cast that back-and-forth to a fancy pointer type, why not avoid storing a fancy pointer entirely and just store a raw pointer? Fancy pointers and raw pointers are meant to have lossless round-trip conversions between them anyway, so we shouldn’t lose any information.

Originally I wrote this article believing that I needed many customization points to make this work, including to_address(), next(), dereference(), compare_with_null(), and pointer_to(). Now I had a new approach:

- Don’t try to store a fancy pointer type. Just store a

<Variable> called p_ initialized with to_address(arrays.elements_). This will be of type value_type*, so there’s no issue to store it, and we don’t lose any information.

- Whenever I need to dereference

p_ and grab the element, just do this directly. Since p_ is a raw pointer in all cases, then this operation is fine. No need for a dereference() customization point.

- Whenever I need to compare

p_ with nullptr, just do this directly as well. For a similar reason, there is no need for a compare_with_null() customization point.

The next() customization point was a bit more complicated to deal with. In the end I decided to have next() be defined like this:

<!-- Inside the container implementation in Boost.Unordered itself -->

<Intrinsic Name="next" Optional="true" Expression="((arrays_type::value_type_pointer)p) + n">

<Parameter Name="p" Type="arrays_type::value_type*" />

<Parameter Name="n" Type="ptrdiff_t" />

</Intrinsic>

<Intrinsic Name="next" Optional="true" Expression="((arrays_type::value_type_pointer*)nullptr)->boost_next(p, n)">

<Parameter Name="p" Type="arrays_type::value_type*" />

<Parameter Name="n" Type="ptrdiff_t" />

</Intrinsic>

<!-- Inside the fancy pointer type, as a customization point -->

<Intrinsic Name="boost_next" ReturnType="pointer" Expression="...">

<Parameter Name="ptr" Type="pointer" />

<Parameter Name="offset" Type="difference_type" />

</Intrinsic>

Here is the key to this customization point boost_next: It takes in a raw pointer and returns a raw pointer. The conversion to and from the fancy pointer is done inside the expression, where the author has the most information about their type, and can do low-level operations that emulate converting back and forth. This means we don’t even need the pointer_to() customization point! So this takes us to only 2 total customization points.

Similarly to to_address(), I needed a way to ensure that the raw pointer overload fails to parse when we’re using fancy pointers. Here I did that by calling (arrays_type::value_type_pointer)p. When we’re using raw pointers, this will be a no-op. When we’re using fancy pointers, this will fail because we can’t cast from a raw pointer to a class type.

This customization point boost_next() is meant to be called as a static function. However, there’s no way to call type::foo() for an intrinsic in natvis. Even though it doesn’t look pretty, dereferencing a nullptr seems like the best way forward.

Conclusion

I originally ended the main body of this article with a defeat, but now I can claim a victory!

With Boost 1.86, Boost.Unordered’s open-addressing containers will come with visualizations in the Visual Studio Natvis framework, along with other things. Initially in 1.86, we only support containers with allocators that use raw pointers. Natvis support for containers using fancy pointers will come in Boost 1.87.

To prove that the fancy pointer implementation works, I wrote the proper customization points for boost::interprocess::offset_ptr. All you need is an intrinsic called boost_to_address() and another one called boost_next(), then any container using your fancy pointer type can be visualized too! I wrote detailed instructions for fancy pointer support at the bottom of the boost_unordered.natvis file, in case you’re interested in implementing this customization point for your type.

With this article, I hope you have learned some more intricacies of how to write a natvis file. It has been a great experience to explore what is and what is not possible. We can write some fairly complicated algorithms and overload sets. It seems like natvis can even be used for arbitrary data with customization points for users to inject behaviour. This is not without limitation, but there is quite a lot that we can do.

Next I plan on embarking on the same journey but for GDB pretty-printers. If all goes well, or if it completely fails, I’ll write about it.

If you have been along for the journey, thank you for reading!